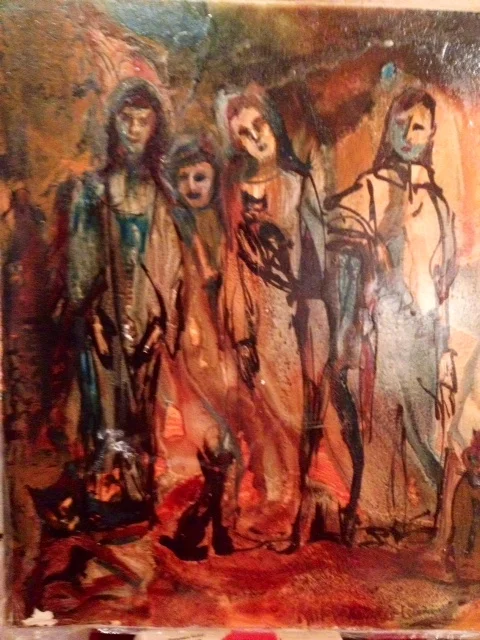

I call it Four Women--by Bettie Friendenberg

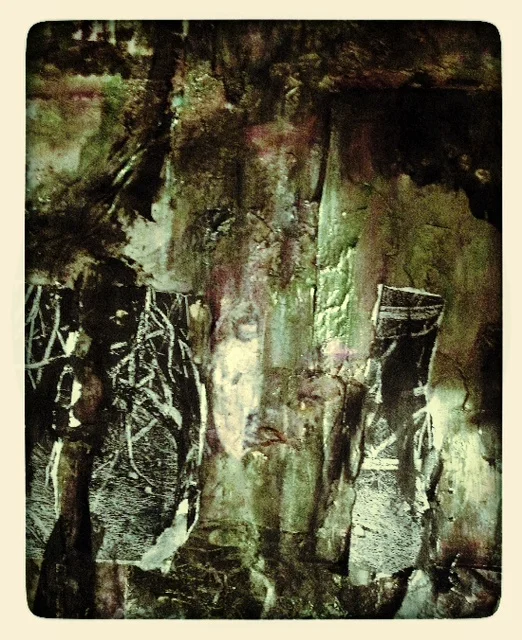

Gold Buttons, Marsha Recknagel

I have not written a post in so long that I forgot my password to log into the site.

When I remembered--after some scary seconds--I was heartened: it was a sign. First, a sign that my memory is intact. A sign, also, that I should write. Write to you, from me to you. Hello. Hello.

All my thoughts were random thoughts. But I decided to throw them down like pick-up sticks and see if there could be something to arise out of the random jumble of ideas.

Always, I think, this "post" doesn't have to have a middle and end--of course it must have a beginning. And so it begins......

Perhaps I'll escape my training and leave dangling ends to be picked up later in what should be an ongoing conversation. What will be an ongoing conversation. Already it has started, today, with Marc from WheelchairKamikaze.

Marc runs an MS blog that I visit now and again. Marc has a truly debilitating form of MS. Some neurologists don't think that what he has is, in fact, MS, but they don't know what it is, except horrible. Marc writes a lot about his twenties, years he believes he wasted by being depressed, dissatisfied, angry, and self-destructive. I always want to shout at him--Don't waste time in anger, in regret. He knows this already, but he spends a great deal of time immobile and so thinking is what he does.

He wrote a scene from his life that was like nothing he'd written before, and it has stayed with me. He said that once he had tried to straighten himself out, hold himself erect to stand and untwist his left arm, get his right leg to appear to be the same strength as his left. He managed to get out of his wheelchair and posed just long enough to see himself in the mirror, to see himself whole.

This was what Marc wanted--to capture an image to hold onto so he could remember who he had been.

I can't imagine such a triumph of will or such a yearning to be put back together again.

Two months ago I had another neurological exam in which the drill was sickeningly familiar. I tried not to try this time. I wanted to see what would happen if I didn't concentrate. The doctor had me close my eyes and walk toe to heel. I swayed as if on a rocking boat, and he put out his hands to catch me before I fell. He said, That's good. That's not bad.

Was he kidding?

And why didn't I ask him if he were kidding?

A couple of years ago someone I love said to me --You didn't make this happen to you. Piercing my heart with her knowledge of my heart, she pressed me--You think that, don't you? That you brought this on yourself?

Yes, I'd thought that. I'd thought my wild ways had made my body a good host for this mysterious illness. But I was ready to reframe and put an end to this particular mind-worm. I'd just needed some shock therapy, which my friend delivered. I'd pondered the why and wherefores of my MS for many sleepless nights, for long hours on a plane, driving a car, washing dishes, taking baths. She reminded me about the art of reframing, the way one can shift perspectives and dislodge the old way of seeing things when seen from a different angle. Just like Marc with his mirror, I wanted to create a new way to see myself.

It was during this shifting and shuffling around the idea of how I'd come to think about MS and "our" relationship that I returned to another time in my life, a time when standing or sitting or bending was almost unbearable. I could be flat out on the floor with some relief, and actually, it's funny to remember that walking was easier than standing, and much easier than it is now.

I'd rarely thought about the back pain I'd had before being diagnosed with MS. Suddenly there were the details, the memory of dropping something on the floor and deciding to leave it there, whatever it was--a banana peel, a banana! There were other things scattered around the house that I'd decided to step over instead of bending over to retrieve.

Suddenly the whole damn siege of the nightmare of my back pain was right there on the tip of my mind. The mind makes one forget pain once it is gone. Onto the new pain!! I've heard that anyone who has had a baby knows very well the tricks of the mind concerning pain. This amnesia seems important to the survival of the species.

From July 2001 until around 2005, I'd had agonizing back pain, and over that time I'd become an expert on back pain. Elaine Scarry's On Pain is a well-worn book on my shelf. During those years, I'd had three epidurals, wore a tens-unit, had acupuncture, took bottles and bottles of pills: hydrocodone, Advil, trazodone, valium, Ambien. I'd worn powerful numbing patches, had a regular appointment with the chiropractor until she realized she was hurting more than helping so she turned me over to the resident massage therapist. I had one laminectomy that was a success until my disc reherniated--one in a thousand were the odds of such a thing, or so lamented the back surgeon--a very nice woman who hit herself on the forehead with her hand and said, Why didn't this happen to that jerk patient? This laminectomy--an emergency one-- rendered me almost immobile, leaving me with the feeling that concrete had been poured into the small of my back.

Not long after this surgery, I went to a tiny island off the coast of Honduras to try to heal myself. I wanted to live without a car--getting in and out of a car was living hell--and I wanted to be able to swim daily in the ocean. While on Utila, I swam in the mornings and made myself walk each afternoon from one end of the island to the other, using my sun umbrella as a cane.

Still each night I could not turn over in bed without screaming.

One day by a pure accident of fate, I met some doctors who went each year from the States to Honduras to help the poor Hondurans who do back-breaking work--the doctors treated their weeping leg wounds by blocking off the veins providing the blood supply to such wounds. And, it turned out, they also used a method called prolotherapy to alleviate back pain.

I had this treatment twice in La Ceiba, on the mainland. Eight needles full of a certain mixture were stuck across my lower back--you can read about this if you do a Google search of prolotherapy.

Hondurans come from all parts of the country to stand in line to get this annual doctoring. I visited the Red Cross camp with all the others -- and so in an open-air MASH-like set-up with frayed sheets hung with clothespins for privacy, my naked butt was exposed to the brilliant blue sky, my diaphanous skirt bunched around my waist.

After I returned to the States. I followed up with a doctor in Austin who specialized in pain management, using prolotherapy mainly to help burn victims at the Shriner Children's Hospital. He'd always bring me a handful of medical journal articles about prolotherapy for me to read while I waited an hour after the injections before I got up from the table where he'd injected my back.

After eight sessions over a six-month period, I was pain free for the first time in years.

I tell you this to establish my credentials as an expert in back pain.

I often hear people say--My back just went out! As if it happened that second.

What seems like a sudden event is actually the last straw of thousands of incremental insults.

This I learned.

So this is why I thought I "got" MS. I had not treated my body as a DIVINE TEMPLE!! I'd pitched myself headlong into life--breaking bones, hearts (my own included). I had been reckless.

Yet, I am reconditioning myself, reframing, changing out the old story for a new one. In this one I have a memory that slips through the sieve of my mind in and out flashing at odd times throughout the last forty years.

I was working at Texas Research Institute for Mental Sciences in the Texas Medical Center in Houston. My supervisor--Lore--the head of public relations at TRIMS for whom I worked as "an editorial assistant"--had told me about a young woman she wanted me to meet. Baylor College of Medicine was across the street from TRIMS and there were many exchanges between us--feature stories to pursue for our newsletter.

Lore had learned of a new study in the Department of Neurology at Baylor and because our center had some interns who worked at both Baylor and TRIMS, she was going to write about the Baylor study.

That is why one day there was the woman standing in my doorway. She was only a few years older than me; she was beautiful, thin and delicate. Her fragility was a high-pitched hum around her. She looked somewhat like Twiggy: she had long straight blonde hair, a pale oval sweet face with large blue eyes and translucent skin. And she had a cane.

I am ashamed about the way I romanticized her. I was told she had Multiple Sclerosis.

There was somewhat of a scandal surrounding her--she had gone to Baylor to participate in the MS study, and her doctor fell in love with her, left his wife, and now lived with her in Montrose, not far from where I lived. This swaying vulnerable stalwart heroic figure stood in my doorway and imprinted herself permanently in my memory. Oh how many times I've thought of her since I was diagnosed.

It was also whispered that she didn't have long to live, which made her shimmering self seem to shine brighter than a regular old beautiful petite blonde.

This was l977.

I have to brush the image of her aside in order to reframe my story.

I have a slow progressing MS.

Perhaps I would have had a fast-paced disease if I hadn't done lots of yoga, lots of men, lots of drugs, lots of alcohol.

A strange but true frame: my MS could have been worse if I had not lived so fully, so passionately.

Last night I was on the phone with an old friend--a man who has known me since I was fourteen--and I told him that my assistant had asked me what I had in mind about the future of my artwork. I told him that others had suggested I get an agent, think about a show. He said, You don't want that do you?

I said no, I didn't want that, but I didn't know what I wanted.

He said, "Well, if you were forty and didn't have MS you might have wanted that."

I said, "Mainly I want to be forty and not have MS."

What I want, and what I once wanted, and what I got use to wanting over time is so different from what I think I want now that I'm often confused about WHAT I WANT.

I continually am brought up short by the realization that what once made me happy doesn't really do it for me anymore.

I also once absolutely was insane for onion dip and fritos and for a lark I tried that particular combo of horrors a few months back, and it will come as no surprise that it didn't do it for me anymore.

I watched the documentary on Susan Sontag this afternoon--instead of Christmas shopping, instead of going to the Y. This is what I wanted--to spend a whole day in solitude, painting, watching TV, paying attention to what I liked to do now in this new state of being.

A black and white photograph of Sontag flashed on the screen. There she was in my living room--in her boots and black sweater on the book jacket of her second book. This image brought such a cascade of blunt force trauma memories that I had to push "pause" and take a break. I had used that book to get HERE. Against Interpretation, Etc. Her sexy smart self had gazed out from that cover at me for years when I was young and wanting.......to find my way in the world.

I'd first seen this book when I was twenty-two years old, newly living in Houston, and working in a used bookstore on S. Shepard run by a very strange and dirty old man named John Lyman. I won't even go into the strange and dirty parts right now because that is another essay. But this was where I discovered all the amazing books and all the amazing women writers I'd not discovered in college--I went to LSU where being an intellectual was frowned upon. Merely studying was looked upon as an odd "pastime." This book was at the bookstore where I also discovered Colette and Anais Nin and Doris Lessing and Isak Dinesen. How could I ever have imagined that someday Sontag's close friend, Richard Howard, would be one of my closest friends?

I also discovered Lillian Hellman's memoirs on Mr. Lyman's shelves and twenty years later I'd write a dissertation on these works.

I recently had some of my artwork appear in a group show, and Richard and his partner David came to town for the opening. Richard had been one of my first writing mentors and had seen me through draft after draft of my memoir. David is a painter. Over many years, I'd visit them in NYC, and I'd known they were disappointed in me because I never wanted to accompany them to museums or galleries. This was mainly because of THE BACK PAIN, but also because I was so ignorant about the ways to speak about art.

Not much surprises Richard--he has a way of asking one questions, of listening to the answers--that makes him get a quick and pretty accurate profile of people. My new life of making art has completely taken him by surprise. He has asked me not a few times--Did you KNOW you could do this?

Yes and no.

I just knew I wanted to.

When I was in the second grade my mother signed me up for an art class that met on Saturdays in a building on the edge of downtown Shreveport within feet from the Red River.

I can recall the smell of the slow-moving sludge of a river, remember the steps that led up to the studio that smelled like a boathouse, a filling station, and a hardware store--the three of my favorite establishments.

The art teacher was named Mrs. Friedenberg. Bettie Friedenberg. On the first day, she handed me some pliers and tiles and told me to break up the tiles and then cement the tiles onto a board. I was left alone to accomplish this task, sitting on a stool, the table in front of me richly layered with dollops and drips of paint. I don't think I need to tell you that I felt as if I had been delivered into heaven on earth.

This story could take a bad turn right now, and it has in the past. The worn-stone-of-a-story is that my mother took me out of the class because it was too much for her to drop me off and come back to get me. But now I can see her side of the story. She had two older daughters and a younger son. My oldest sister had two children and was a single mother at eighteen. She'd lived at our house because she was divorced from the guy with whom she got pregnant when she was sixteen. My poor mother. All had gone to hell in her life. My father had not wanted children--surprise surprise--which was what my mother wanted with all her heart. Then she got her way and had "her" family, and of course every mistake, every sorrow, every mishap was thrown in her face as a "I told you so."

One afternoon of art class must have seemed one place that she could dial back and have a bit more time--to grocery shop, to prepare dinner, something she pretty much hated to do but she did it night after night after night after night.

I just told my hairdresser that I had never made a Thanksgiving dinner, never cooked a turkey and that this was on my bucket list of things NOT TO DO before I died.

What I have done--some years before I'm dead--is go back up those stairs in my imagination and sit on that stool and run my hand over splatters of paint, but this time the Rorschach blots of paint are made by me.

When I was fourteen, I fell in love with a long-haired, skinny, smart boy named Geoff. In l968 I went to his house for Thanksgiving dinner. When I opened the front door, I entered a small foyer. Right in front of me was beautiful piece of furniture over which hung a beautiful painting. I looked at the signature at the bottom right corner of the painting and there it was--Bettie Friedenberg. That day Geoff's mother told me that it was a "collage." Years later, Geoff's mother moved from the house into a townhouse and gave me the painting--the collage. I love this work. And I have continued to love Geoff Pike, who remains a dear friend.

Tonight I went out to my studio and looked at the collage.

These four women, images created from tissue paper and oil paint, have stared out at me since before i ever bought brushes and paint. They were in my first home, hanging in a place I could see when I talked on the phone. I've studied them over my lifetime, through the words and stories and plans made with friends I'd stared at them. They stared back.

Certainly a mirror of sorts.

Here I've attached Friedenberg's piece as well as one of mine that I finished this morning. Something, I believe, has been exchanged, something between me and the woman who gave me this painting, something between me and the woman who created these women, and between me and this creation. What do I want? I want to create something that holds the gaze of a viewer until she knows who I am, whole, and who she is, and maybe who she can be in the future.